The White House

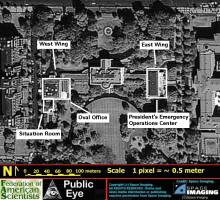

President's Emergency Operations Center - PEOC

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

Washington, DC

Below the East Wing of the White House, lies the President�s Emergency

Operations Center (PEOC), which exists to handle nuclear contingencies. The PEOC is differentiated from the White House Situation Room which is located in the basement of the West Wing of the White House.

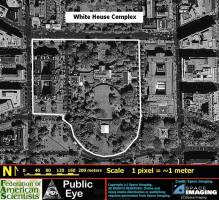

The White House Complex

General Layout

West Wing Office Space Layout, circa 1990

The White House is the oldest public building in the District of Columbia, and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is the most famous address in the United States. Here every President, except George Washington, has conducted the government of the Nation. In the past 200 years, the White House has become symbolic of the American Presidency throughout the world. While the Capitol represents the freedom and ideals of the Nation, the White House stands for the power and statesmanship of the chief executive.

The White House itself has been altered, adapted, or enlarged to suit the needs of the presidents and the demands of a growing Nation and of a more complicated world. Throughout all the changes, the basic structure has been honored. Following the British burning in 1814, the house was rebuilt between 1815 and 1817 on the same walls.

When Theodore Roosevelt became President one of the first things he did was to change the name of the structure to the White House. Since the mid-19th century it had been called the Executive Mansion, and before that it had been described in government documents as the President's House. But almost from the beginning it was known popularly as the White House; certainly that name predated the fire of 1814. In 1901 Roosevelt made it official.

Roosevelt faced major problems, for he found that the house needed extensive structural repairs, more space for both the family and the staff was required, and the interior was a conglomeration of styles. Congress appropriated money to repair and refurnish the house and to construct new offices for the President. The State Dining Room was enlarged and space for presidential staff in an executive office building (the West Wing) replaced the old conservatories. Work began in June 1902 under the supervision of the architectural firm of McKim Mead, and White. By the end of the year the job was complete.

Despite the great amount of work done in 1902, demands for more space grew, and in 1909 the West Wing offices were enlarged and the well-known Oval Office built. Prior to construction of the West Wing different Presidents hag used various arrangements of rooms in the mansion for their offices. Since 1909 the Oval Office has been the President's Office. Outside the Oval Office is the Rose Garden. The 1902 renovations made this space available for a formal garden. Roses were first planted here in 1913. A third floor was added in 1927 to provide more living space in the residence. In 1934 Franklin Roosevelt again had the West Wing enlarged. Once the United States entered World War II, the East Wing and an air raid shelter were built and a movie theater was installed in the east terrace. In 1948. Harry Truman added a balcony to the south portico. And the greatly weakened structure was completely rebuilt within its original walls in 1948-52.

The White House is the oldest public building in the District of Columbia, and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is the most famous address in the United States. Here every President, except George Washington, has conducted the government of the Nation. In the past 200 years, the White House has become symbolic of the American Presidency throughout the world. While the Capitol represents the freedom and ideals of the Nation, the White House stands for the power and statesmanship of the chief executive.

The White House itself has been altered, adapted, or enlarged to suit the needs of the presidents and the demands of a growing Nation and of a more complicated world. Throughout all the changes, the basic structure has been honored. Following the British burning in 1814, the house was rebuilt between 1815 and 1817 on the same walls.

When Theodore Roosevelt became President one of the first things he did was to change the name of the structure to the White House. Since the mid-19th century it had been called the Executive Mansion, and before that it had been described in government documents as the President's House. But almost from the beginning it was known popularly as the White House; certainly that name predated the fire of 1814. In 1901 Roosevelt made it official.

Roosevelt faced major problems, for he found that the house needed extensive structural repairs, more space for both the family and the staff was required, and the interior was a conglomeration of styles. Congress appropriated money to repair and refurnish the house and to construct new offices for the President. The State Dining Room was enlarged and space for presidential staff in an executive office building (the West Wing) replaced the old conservatories. Work began in June 1902 under the supervision of the architectural firm of McKim Mead, and White. By the end of the year the job was complete.

Despite the great amount of work done in 1902, demands for more space grew, and in 1909 the West Wing offices were enlarged and the well-known Oval Office built. Prior to construction of the West Wing different Presidents hag used various arrangements of rooms in the mansion for their offices. Since 1909 the Oval Office has been the President's Office. Outside the Oval Office is the Rose Garden. The 1902 renovations made this space available for a formal garden. Roses were first planted here in 1913. A third floor was added in 1927 to provide more living space in the residence. In 1934 Franklin Roosevelt again had the West Wing enlarged. Once the United States entered World War II, the East Wing and an air raid shelter were built and a movie theater was installed in the east terrace. In 1948. Harry Truman added a balcony to the south portico. And the greatly weakened structure was completely rebuilt within its original walls in 1948-52.

Old Executive Office Building (OEOB)

Next door to the White House, the Old Executive Office Building (OEOB) was designed by Supervising Architect of the Treasury, Alfred B. Mullett. It was built from 1871 to 1888 to house the growing staffs of the State, War, and Navy Departments, and is considered one of the best examples of French Second Empire architecture in the country. In bold contrast to many of the somber classical revival buildings in Washington, the OEOB's flamboyant style epitomizes the optimism and exuberance of the post Civil War period.

The State, War, and Navy Building, as it was originally known, housed the three Executive Branch Departments most intimately associated with formulating and conducting the nation's foreign policy in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth century -- the period when the United States emerged as an international power. The building has housed some of the nation's most significant diplomats and politicians and has been the scene of many historic events.

The history of the OEOB began long before its foundations were laid. The first executive offices were constructed on sites flanking the White House between 1799 and 1820. A series of fires (including the burning by the British in 1814) and overcrowding conditions led to the construction of the existing Treasury Building, and in 1866, the construction of the North Wing of the Treasury Building necessitated the demolition of the State Department to the northeast of the White House. The State Department then moved to the District of Columbia Orphan Asylum while the War and Navy Departments continued to make do with their cramped quarters to the west of the White House.

In December of 1869, Congress appointed a commission to select a site and prepare plans and cost estimates for a new State Department Building. The commission was also to consider possible arrangements for the War and Navy Departments. To the horror of some who expected a Greek Revival twin of the Treasury Building to be erected on the other side of the White House, the elaborate Second Empire design of Alfred Mullett was selected, and construction of a building to house all three departments began in June of 1871.

Construction took 17 years as the building slowly rose wing by wing. When the OEOB was finished in 1888, it was the largest office building in Washington, with 1.4 meter granite walls, 4.9 meter ceilings, and nearly 3 kilometers of black and white marble tile corridors. Almost all of the interior detail is of cast iron or plaster; the use of wood was minimized to insure fire safety. Monumental curving staircases of granite with over 4,000 individually cast bronze balusters are capped by four skylight domes and two stained glass rotundas.

Completed in 1875, the State Department's south wing was the first to be occupied, with its elegant four-story library, Diplomatic Reception Room, and Secretary's office decorated with carved wood, Oriental rugs, and stenciled wall patterns. The Executive Office of the President Library was originally the State Department's Library. This room was constructed entirely of cast iron in 1875.

The Navy Department moved into the east wing in 1879, where elaborate wall and ceiling stenciling and Parquetry floors decorated the office of the Secretary. The two-story Indian Treaty Room, originally the Navy's library and reception room, cost more per square meter than any other room in the building because of its rich marble wall panels, 360 kilogram bronze sconces, and gold leaf ornamentation. This room has been the scene of many Presidential news conferences and continues to be used for conferences and receptions attended by the President.

The remaining north, west, and center wings were constructed for the War Department and took an additional 10 years to build. Notable interiors include an ornate cast iron library, the Secretary's suite, and the stained glass skylight over the west wing's double staircase.

Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Dwight Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson, Gerald Ford, and George Bush all had offices in this building before becoming President. It has housed 16 Secretaries of the Navy, 21 Secretaries of War, and 24 Secretaries of State. President Herbert Hoover occupied the Secretary of Navy's office for a few months following a fire in the Oval Office on Christmas Eve, 1929. In recent history, President Richard Nixon had a private office here. Vice President Lyndon Johnson was the first in a succession of Vice Presidents to the present day that have had offices in the building.

Gradually, the original tenants of the OEOB vacated the building - the Navy Department left in 1918 (except for the Secretary who stayed until 1923), followed by the War Department in 1938, and finally by the State Department in 1947. The White House began to move some of its offices across West Executive Avenue in 1939, and in 1949 the building was turned over to the Executive Office of the President and given its present name. The building continues to house various agencies that comprise the Executive Office of the President, such as the White House Office, the Office of the Vice President, the Office of Management and Budget, and the National Security Council.

The Second Empire style originated in Europe, where it first appeared during the rebuilding of Paris in the 1850s and 60s. Based upon French Renaissance prototypes, such as the Louvre Palace, the Second Empire style is characterized by the use of a steep mansard roof, central and terminal pavilions, and an elaborately sculptured facade. Its sophistication appealed to visiting foreigners, especially in England and America, where as early as the late 1850s, architects began adopting isolated features and, eventually, the style as a coherent whole. Alfred Mullett's interpretation of the French Second Empire style was, however, particularly Americanized in its lack of an ornate sculptural programmer and its bold, linear details.

While it was only a project on the drafting table, the design of the OEOB was subject to controversy. When it was completed in 1888, the Second Empire style had fallen from favor, and Mullett's masterpiece was perceived by capricious Victorians as only an embarrassing reminder of past whims in architectural preference. This was especially the case with the OEOB, since previous plans for a building on the same site had been in the Greek Revival style of the Treasury Building.

In 1917, the Commission of Fine Arts requested John Russell Pope to prepare sketches of the State, War, and Navy Building that incorporated Classical facades. During the same year, Washington architect Waddy B. Wood completed a drawing depicting the building remodeled to resemble the Treasury Building. This project was revived in 1930, but funds were cut, due to opposition to the project and financial burdens imposed by the Great Depression. In 1957, President Eisenhower's Advisory Committee on Presidential Office Space recommended demolition of the Executive Office Building and construction of a modern office facility. However, the overwhelming expenses associated with the demolition saved the building.

The building has not been without detractors. It has been referred to as Mullett's "architectural infant asylum" by writer Henry Adams. President Harry S. Truman came to the defense of the building when it was threatened by demolition in 1958. He said it was "the greatest monstrosity in America." Noted architectural historian Henry Russell Hitchcock, however, described it as "perhaps the best extant example in America of the second empire." The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1969. In 1972, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites.

Since 1981, the Office of Administration of the Executive Office of the President has actively pursued a rigorous program of rehabilitation of the OEOB to put an end to the deterioration that over the years has taken place throughout this historic building. The entire structure has benefitted from an upgraded maintenance program that has also included restoration of some of the OEOB's most spectacular historic interiors. In 1983, the Office of Administration Preservation Office was instituted to oversee this effort and to develop a comprehensive preservation program, which includes restoration, research, educational programs, public tour program, and the formulation of a master plan for the building's continued adaptive use.

Sources and Resources

- The President's Secure Telephone, letter to President Kennedy, September 18, 1961

- Intelligence Inside the White House: The Influence of Executive Style and Technology [PDF], By David A.Radi, March 1997, Center for Information Policy Research, Harvard University

- Nuclear Battlefields, Global Links in the Arms Race, William M. Arkin, Richard W. Fieldhouse

- Managing Nuclear Opearations, Ashton B. Carter, John D. Steinbruner, Charles A. Zraket, Eds.

http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/usa/c3i/peoc.htm

Created by John Pike

Maintained by Steven Aftergood

Updated Tuesday October 2, 2000