As the Nike Ajax system underwent testing during the early 1950s, the Army became concerned that the missile was incapable of stopping a massed Soviet air attack. To enhance the missile�s capabilities, the Army explored the feasibility of equipping Ajax with a nuclear warhead, but when that proved impractical, in July 1953 the service authorized development of a second generation surface-to-air missile, the Nike Hercules. As with Nike Ajax, Western Electric was the primary contractor with Bell Telephone Laboratories providing the guidance systems and Douglas Aircraft serving as the major subcontractor for the airframe.

In 1958, 5 years after the Army received approval to design and build the system. Nike Hercules stood ready to deploy from converted Nike Ajax batteries located in the New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago defense areas. However, as Nike Hercules batteries became operational, the bitter feud between the Army and Air Force over control of the nation�s air defense missile force flared anew. The Air Force opposed Nike Hercules, claiming that the Army missile duplicated the capabilities of the soon-to-be-deployed BOMARC. Eventually, both of the competing missiles systems were deployed, but the Nike Hercules would be fielded in far greater numbers over the next 6 years.

As the Nike Ajax system underwent testing during the early 1950s, the Army became concerned that the missile was incapable of stopping a massed Soviet air attack. To enhance the missile�s capabilities, the Army explored the feasibility of equipping Ajax with a nuclear warhead, but when that proved impractical, in July 1953 the service authorized development of a second generation surface-to-air missile, the Nike Hercules. As with Nike Ajax, Western Electric was the primary contractor with Bell Telephone Laboratories providing the guidance systems and Douglas Aircraft serving as the major subcontractor for the airframe.

In 1958, 5 years after the Army received approval to design and build the system. Nike Hercules stood ready to deploy from converted Nike Ajax batteries located in the New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago defense areas. However, as Nike Hercules batteries became operational, the bitter feud between the Army and Air Force over control of the nation�s air defense missile force flared anew. The Air Force opposed Nike Hercules, claiming that the Army missile duplicated the capabilities of the soon-to-be-deployed BOMARC. Eventually, both of the competing missiles systems were deployed, but the Nike Hercules would be fielded in far greater numbers over the next 6 years.

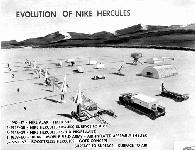

In the late 1950s early 1960s, surface-to-air missile batteries were placed for the first time around such cities as St. Louis and Kansas City and around several Strategic Air Command (SAC) bomber bases. Unlike the older sites, these batteries were placed in locations that optimized the missiles� range and minimized the warhead damage. Nike Hercules batteries at SAC bases and in Hawaii were installed in an outdoor configuration. In Alaska, a unique above-ground shelter configuration was provided for batteries guarding Anchorage and Fairbanks. Local Corps of Engineer Districts supervised the conversion of Nike Ajax batteries and the construction of new Nike Hercules batteries.

Nike Hercules first entered service on June 30, 1958, at batteries located near New York. Philadelphia, and Chicago. The missiles remained deployed around strategically important areas within the continental United States until 1974. The Alaskan sites were deactivated in 1978 and Florida sites stood down during the following year. Although the missile left the U.S. inventory, other nations maintained the missiles in their inventories into the early 1990s and sent their soldiers to the United States to conduct live-fire exercises at Fort Bliss, Texas. Converted sites received new radars and underwent modifications so the new missiles could be serviced and stored. Because of the larger size of the Nike Hercules, an underground magazine�s capacity was reduced to eight missiles. Thus, storage racks, launcher rails, and elevators underwent modification to accept the larger missiles. Two additional features that readily distinguished newly converted sites were the double fence and the kennels housing dogs that patrolled the perimeter between the two fences. New sites, located away from populated areas did not have to be confined in acreage. Consequently, these batteries were all above ground with missile storage and maintenance facilities located behind earthen berms. Not all sites received the complete Improved Hercules package. HIPAR radars were denied to some sites due to geographical constraints and/or to avoid duplication of radars located at adjacent sites.

Specifications | |

| Length | 41 feet |

| Diameter | 31.5 inches |

| Wingspan | 6 feet, 2 inches |

| Weight | 10.710 pounds |

| Booster fuel | Solid propellant |

| Missile fuel | Solid propellant |

| Range | Over 75 miles |

| Speed | Mach 3.65 2,707 mph |

| Altitude | Up to 150,000 feet |

| Guidance | Command by electronic computer and radar |

| Warhead | High-Explosive fragmentation or nuclear |

| Contractors |

|