International Game ’99:

Crisis in South Asia

28

-30 January 1999

Bradd C. Hayes

Sponsored by the

United States Naval War College

This report was prepared for the Decision Support and Strategic Research Departments of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies. The contents of the report reflect the views of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Naval War College or any other department or agency of the United States Government.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank James Harrington, Lawrence Modisett, William Piersig, Andres Vaart, and Paul Taylor for providing thoughtful comments on early drafts of this report. The scenario material was drawn from Professor Vaart's background briefings, and Professor Piersig's game book provided much of the material contained in the Appendices.

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY *

BACKGROUND *

The South Asia Proliferation Project *

The International Game Series *

Game Vision and Objectives *

Background *

The Setting: July 2003 *

GAME PLAY *

MOVE ONE SCENARIO *

Move One ¾

Initial Positions *

Move One ¾

Negotiations *

MOVE TWO SCENARIO *

Move Two ¾

Initial Reactions *

Move Two ¾

Negotiations *

Move Two ¾

Outcomes *

OUT OF ROLE DISCUSSIONS *

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS *

International organizations are likely to be ineffective in addressing a nuclear crisis in South Asia. *

For the foreseeable future, "managed tension" will be the norm. *

Historic ties shape perspectives. *

Conventional force confidence-building measures need to be complemented by nuclear CBMs. *

Nuclear weapons provide states with enhanced negotiating leverage. *

Conflicting views concerning nuclear weapons will continue. *

Post-nuclear exchange options are extremely limited. *

POLICY IMPLICATIONS *

Pursue sources of leverage and be willing to use it. *

Pre-crisis sanctions weaken, rather than strengthen, international leverage *

Leverage weakens as a crisis escalates. *

Terrorism can precipitate interstate conflict. *

The International community should be more proactive. *

Non-proliferation and comprehensive test ban treaties are more likely to delay than halt the of spread nuclear weapons. *

Unilateral options are unlikely to work. *

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS *

APPENDIX A: INDIA/PAKISTAN: MILITARY ASSUMPTIONS IN 2003 *

APPENDIX B: INDIA -

PAKISTAN CHRONOLOGY *

APPENDIX C: INDIA COUNTRY PROFILE *

APPENDIX D: PAKISTAN COUNTRY PROFILE *

APPENDIX E: INDIA AND PAKISTAN SANCTIONS *

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The primary purpose of this game was to explore international approaches for dealing with crises involving the threat and use of nuclear weapons. To do so, the game engaged mid- to high-level participants from fifteen countries in a United Nations Security Council setting. The scenario examined tensions between India and Pakistan. The following observations emerged from game play:

- International organizations are likely to be ineffective in addressing a nuclear crisis in South Asia, primarily because their deliberations take too long. However, a forum like the United Nations will still be required for the conduct of critical multilateral negotiations, whether or not the organization itself gets involved in intervention.

- For the foreseeable future, "managed tension" will remain the norm between India and Pakistan.

- Historic ties shape the perceptions and actions of belligerents as well as those responding to a crisis. Although this may sound like a blinding flash of the obvious, the extent to which historic ties impacted the game was revealing.

- Conventional force confidence-building measures between India and Pakistan need to be complemented by nuclear CBMs.

- Nuclear weapons provide states with enhanced negotiating leverage. Nuclear weapons provide countries with a wild card that they would not otherwise possess.

- Conflicting views concerning the importance of nuclear weapons will continue. India, in particular, sees possession of nuclear weapons as the key to great power status.

- Post-nuclear exchange options are extremely limited.

Game play also revealed a number of policy implications that should be considered by U.S. decision-makers. They include:

- The U.S. must pursue more sources of leverage that could be used to prevent a crisis from escalating and understand how to employ them aggressively.

- Pre-crisis sanctions and embargoes generally weaken, rather than strengthen, the international community's bargaining position.

- Policymakers must recognize that leverage weakens as a crisis escalates.

- Terrorism can precipitate interstate conflict.

- The international community needs to be more proactive in dealing with festering tensions among nuclear powers. The challenge in South Asia remains Kashmir.

- Unilateral options are unlikely to work. U.S. actions were accepted only as long as they were developed in partnership with others.

- Non-proliferation and comprehensive test ban treaties are more likely to delay than to halt the spread of nuclear weapons. Countries currently pursuing nuclear programs are not likely to renounce them.

Participants agreed that accident and miscalculation are the most likely triggers that could result in a nuclear exchange on the sub-continent. Resort to tactical nuclear weapons is especially likely if a country perceives that its sovereignty is seriously threatened. Participants also asserted that if the international community fails to resolve serious cross-border tensions, and only attempts, on the brink of conflict, to search for solutions, it must bear some responsibility for the suffering that results.

Some players expressed a preference for handling such matters bilaterally, others indicated a preference for a regional resolution; but, for the most part, participants understood that a crisis involving the potential use of nuclear weapons is an international problem. Moralist, pragmatist, and fatalist positions were all represented in the game. Few players believed, however, that the world would be denuclearized in the near term, if ever. Nuclear weapons are like smoke in a bottle; once released, it is impossible to put it back in.

BACKGROUND

The South Asia Proliferation Project

Following the nuclear tests by India and Pakistan in May 1998, Dr. Lawrence Modisett, Director of the Decision Support Department in the United States Naval War College's Center for Naval Warfare Studies (CNWS), initiated a series of simulations to examine international consequences of nuclear developments in South Asia. Events, either scheduled or concluded, consider the implications, economic aspects, and operational factors for U.S. policy. The subject of the current report is international responses to conflict in South Asia. Ambassador Paul D. Taylor, head of the South Asia Proliferation Project, was game director. Preparation of scenarios was the responsibility of Professor Andres Vaart, Advisor to the Dean of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies.

The International Game Series

Now in its sixth year, the International Game Series is sponsored by the United States Naval War College’s Center for Naval Warfare Studies. The Decision Support Department conducted this game with the assistance of the Strategic Research Department, which has conducted all previous games. The games are politico-military simulations designed to explore regional, national and international perspectives on current or future issues of interest to the United States, using primarily non-U.S. players. While generally oriented around international peace and security, the events are not war games; rather, they explore conflict prevention, management, and resolution techniques. Results from the International Game series are made available to personnel within various agencies of the United States’ national security community to help them design and implement better-informed policy. The games are conducted in a completely unclassified manner.

The contribution of International Games lies in the players, who are mid- to high-ranking diplomats, media personnel, and academics from relevant nations. Their career experiences, coupled with their insights on national/regional perspectives, give International Games an authenticity and flavor that cannot be duplicated in any other setting. Players participating in this game were drawn from a number of distinguished academic institutions, agencies, and commands throughout the United States and abroad. Nationals from fifteen nations represented their countries in this game.

The scenario for this game involved a plausible, though not predicted, crisis between India and Pakistan. Because the scenario touched on sensitive issues for many players, the participants were assured of anonymity in any post-game report. Accordingly, country, rather than participant, names have been used throughout this report.

Game Vision and Objectives

This game brought together a uniquely qualified cross section of diplomats, academics, analysts, and military personnel to play a politico-military simulation, in a United Nations Security Council setting, over a day and half. Participants came from the South Pacific and Asia (Australia, China, India, Iran, Japan, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore), Europe (Finland, France, Russia, U.K.), Latin America (Peru), and North America (Canada, US). The game examined issues relevant to a security crisis in South Asia that involved the potential use of nuclear weapons. The primary goal was to explore the roles of the international community as well as individual states in preventing or, failing that, mitigating the effects of such use. Specific objectives were to:

- Explore South Asian security issues and policies.

- Exercise conflict prevention, management, and resolution techniques.

- Examine the political effects of a nuclear exchange.

- Enhance understanding of the opportunities and constraints on national policies.

Background

Participants were introduced to the scenario during an introductory event the evening before the game. It was stressed that the scenario was not intended to predict the future; rather, the scenario was selected because it raised important issues and because it was plausible, worrisome, and consequential. The preconditions posited for the scenario were deemed necessary to instigate crisis. Specific military data, including warhead and missile numbers, represented informed assumptions based on publicly available material. Game orders of battle can be found in Appendix A. In the report, scenario play will be indicated by italic type whereas free game play will be indicated by regular type.

The Setting: July 2003

Economic conditions -

Both India and Pakistan were struggling to recover from the effects of the Asian economic crisis that began in the late 1990s as well as with the effects of year 2000 (Y2K) computer-generated economic problems. Because India was in a better economic position than Pakistan before the Asian economic crisis, it was marginally better positioned coming out of it. The economic crisis fomented significant unrest in both countries, leading to a rise in nationalist fervor and rhetoric. Pakistan's recovery was halted months before the crisis when it found itself suffering from an economic downturn brought on by unwise investments and maladroit economic decisions. This downturn unleashed widespread demonstrations and violence as both prices and unemployment rose.

Economic conditions -

Both India and Pakistan were struggling to recover from the effects of the Asian economic crisis that began in the late 1990s as well as with the effects of year 2000 (Y2K) computer-generated economic problems. Because India was in a better economic position than Pakistan before the Asian economic crisis, it was marginally better positioned coming out of it. The economic crisis fomented significant unrest in both countries, leading to a rise in nationalist fervor and rhetoric. Pakistan's recovery was halted months before the crisis when it found itself suffering from an economic downturn brought on by unwise investments and maladroit economic decisions. This downturn unleashed widespread demonstrations and violence as both prices and unemployment rose.

Security conditions -

Confidence-building measures (CBMs) instituted in the 1990s and before remained in place between India and Pakistan. They included:

- Hotlines to directors general of military operations (December 1990)

- Agreement to avoid attacks on nuclear facilities (January 1991)

- Advance notification of maneuvers (April 1991)

- Agreement to avoid airspace violations (April 1991)

- Prime Ministers’ hotline (1997)

In addition, both India and Pakistan signed and ratified the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CBTB) in 1999 and the Agreement on Fissile Materials Cutoff Treaty in 2002. India had unilaterally declared a policy of "no first use" of nuclear weapons. Although Pakistan’s conventional forces were in a slow decline as a result of economic troubles, a medium-range missile had been tested and improved with Chinese, and possibly North Korean, help. On the Indian side, its military had improved in aircraft, armor, and missiles; much of this was accomplished indigenously or under a long-term agreement signed with Russia in 1998. Both countries had nuclear warheads capable of delivery by either aircraft or missile. Figures 1 and 2 present notional ranges for Pakistani and Indian missiles.

In addition, both India and Pakistan signed and ratified the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CBTB) in 1999 and the Agreement on Fissile Materials Cutoff Treaty in 2002. India had unilaterally declared a policy of "no first use" of nuclear weapons. Although Pakistan’s conventional forces were in a slow decline as a result of economic troubles, a medium-range missile had been tested and improved with Chinese, and possibly North Korean, help. On the Indian side, its military had improved in aircraft, armor, and missiles; much of this was accomplished indigenously or under a long-term agreement signed with Russia in 1998. Both countries had nuclear warheads capable of delivery by either aircraft or missile. Figures 1 and 2 present notional ranges for Pakistani and Indian missiles.

Rebel activity in Kashmir mirrored the violence found elsewhere. Evidence indicated that rebels had been receiving new and better arms, including shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles and remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs) built to carry explosives. Analysts cited in news reports suggested that Pakistani insurgents could not have taken possession of these weapons without the knowledge and acquiescence of the Pakistani government. Dozens of local Kashmiri officials had been assassinated in an apparent attempt to eliminate those loyal to New Delhi. The increased shrillness of rhetoric through the spring of 2003 led to increased troop alerts along the border and to provocative exercises (many of which failed to adhere to notification regimes required by existing agreements). Some of these exercises involved reinforcement of units near the border. As summer deepened, large numbers of combat-ready troops on both sides were deployed relatively far forward.

Rebel activity in Kashmir mirrored the violence found elsewhere. Evidence indicated that rebels had been receiving new and better arms, including shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles and remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs) built to carry explosives. Analysts cited in news reports suggested that Pakistani insurgents could not have taken possession of these weapons without the knowledge and acquiescence of the Pakistani government. Dozens of local Kashmiri officials had been assassinated in an apparent attempt to eliminate those loyal to New Delhi. The increased shrillness of rhetoric through the spring of 2003 led to increased troop alerts along the border and to provocative exercises (many of which failed to adhere to notification regimes required by existing agreements). Some of these exercises involved reinforcement of units near the border. As summer deepened, large numbers of combat-ready troops on both sides were deployed relatively far forward.

GAME PLAY

MOVE ONE SCENARIO

On 1 August 2003, a transport aircraft carrying India’s ministers of interior and defense as well as the army chief of staff exploded as it neared the airport near Srinagar, Kashmir. These leaders, along with 20 staff members, were on their way to an inspection visit in Kashmir’s capital. Eyewitnesses reported that a missile struck the aircraft as it approached the airport. Two days later, on the third of August, India launched Operation Resolute Sword against Kashmiri militants and their support facilities in Kashmir and Pakistan. Indian leaders insisted they were compelled to act, and noted that the assassination of Indian ministers had occurred on the heels of increased cross-border artillery exchanges and a series of terrorist attacks inside India. The Indian government publicly declared that Operation Resolute Sword was limited in both scope and objective and issued an ultimatum demanding the immediate delivery of terrorist leaders being sheltered in Pakistan, the dismantling of known terrorist headquarters and training facilities, and the removal of all Pakistani military forces from Kashmir.

Move One ¾

Initial Positions

In response to the events presented during the scenario briefing, players assembled in a simulated United Nations Security Council to consider the matter. The game design stipulated that both India and Pakistan held seats on the Council. Because the scenario prescribed actions for their countries, the players for India and Pakistan were informed in advance of the general scenario. Aside from the events in the scenario, described above and noted later, all actions, including by the Indian and Pakistani players, were undertaken as free game play at the initiative of the players. The session began with players presenting their country positions.

Pakistan accused India of trying to deflect attention from its inability to control an internal security problem by launching an unwarranted attack against it. Pakistan asserted that it desired a peaceful settlement to the crisis and requested the help of the international community. Later, in response to other countries’ initial statements, Pakistan lamented that, beyond calls for peace, no outrage was expressed concerning Indian aggression.

India dismissed Pakistani charges of aggression and insisted that the crisis was the result of Pakistani-sponsored terrorism. India reiterated that its actions were purely defensive and had to be undertaken because it was clear that further terrorist acts were planned. India reiterated that the operation was strictly limited in scope and objective and that India had no intention of threatening Pakistan’s sovereignty. India stood by all previous demands concerning the dismantling of terrorist facilities.

Canada proposed an immediate cease-fire and recommended approval of a peacekeeping force for the area. It recommended that the Secretary-General take charge of negotiations. Canada also recommended establishing a special commission that could help institute mechanisms for confidence building. To add teeth to its proposal, Canada offered to supply troops. Canada also recommended that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) get involved in some kind of inspection regime. Canada reiterated that it was looking for a new comprehensive approach that encouraged cooperation and development between India and Pakistan.

China expressed concern that India’s operation reflected another step in its long history of expansionist border activity. Although China’s sympathy was clearly with Pakistan, it supported negotiations as long as they were based on national sovereignty. China expressed its historical discomfort with intervention operations and stressed that conflict should be resolved without the further use of force.

Russia supported proposals for a peaceful settlement of the crisis. As a longstanding supporter of India, Russia felt compelled to note that its relationship with India had in no way violated the non-proliferation regime. Russia also noted that countries had the right to protect themselves from terrorist activity. Russia agreed with Canada concerning the advisability of introducing peacekeepers or observers in the area. It also indicated that it was ready to contribute both troops and airlift.

The United Kingdom offered assistance on behalf of the permanent members of the Security Council to enhance military transparency and technical verification between India and Pakistan. The U.K. also recommended the establishment of a fact-finding mission to investigate circumstances surrounding the fatal aircraft incident.

The United States insisted that conflict between two nuclear powers could not be considered a domestic problem. Because of the risk of nuclear exchange, the U.S. urged that a cease-fire be worked out immediately. The U.S. also indicated that it was preparing plans to evacuate American citizens.

Iran pushed for using the immediate crisis as a springboard for launching negotiations that would deal with the underlying causes of tension between India and Pakistan. Iran preferred the two belligerents to work out their differences on their own, but, conceding that that alternative did not look possible, stated that international mediation was the next best option.

Most other members of the Security Council expressed support for the Canadian proposal, believing the underlying causes were so intractable that the two principals would be unable to disengage without help. France, while backing efforts to foster peace, opposed establishing a peacekeeping force. The President of the Security Council (Peru) indicated that enforcement measures under Chapter VII of the UN Charter could be considered, but expressed the hope that it would not automatically be adopted as the best solution. The President urged the Security Council to concentrate on how to bring an immediate end to hostilities. He also urged the belligerents to meet face-to-face to draft a resolution on a cease-fire.

Most other members of the Security Council expressed support for the Canadian proposal, believing the underlying causes were so intractable that the two principals would be unable to disengage without help. France, while backing efforts to foster peace, opposed establishing a peacekeeping force. The President of the Security Council (Peru) indicated that enforcement measures under Chapter VII of the UN Charter could be considered, but expressed the hope that it would not automatically be adopted as the best solution. The President urged the Security Council to concentrate on how to bring an immediate end to hostilities. He also urged the belligerents to meet face-to-face to draft a resolution on a cease-fire.

Following the presentation of initial positions, the meeting was adjourned so that informal consultations could take place. Since Canada had proposed the most comprehensive approach to solving the crisis, it was asked to draft a resolution for further consideration. The Permanent Five met in separate session to work out a unified approach.

Move One ¾

Negotiations

India offered to sign a disengagement agreement with Pakistan and insisted that it had never desired to resolve disagreements by force. Pakistan welcomed India’s offer to cease operations, but expressed displeasure that India did not offer an apology for invading Pakistan in the first place. As noted above, Canada, in consultation with the belligerents, drafted a resolution (shown in the text box) for consideration by the Security Council. After having it read, the President of the Security Council asked if the resolution could be adopted by consensus. Since it committed troops without putting new confidence-building measures in place, several of the Permanent Five states expressed reservations and the resolution was not adopted.

Discussions at the end of the game indicated that had sufficient time been available a version of the resolution acceptable to the Security Council probably could have been drafted. Nevertheless, many of the non-permanent members expressed dismay that an agreement between the belligerents could be held hostage to the whims of the permanent members.

The Canadian proposal for IAEA involvement in the situation was quickly dismissed as an option. The reason for this lack of interest in IAEA involvement was never discussed in open session, although the unhappy experience of the UN inspection team in Iraq was fresh on their minds. Subsequent events prompted Canada to charge that the quick dismissal of this option had far-reaching negative repercussions.

Discussions among the Permanent Five (P5) members of the Security Council ¾

China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States ¾

focused more on providing the belligerents with security guarantees than with establishing an intervention force. Because of the presence of nuclear weapons, some of the P5 suggested that a traditional peacekeeping operation was inappropriate. The Permanent Five, therefore, considered formulations for helping India and Pakistan beef up their air defense and tactical ballistic missile defenses as well as supplying them with improved indications and warning. They also explored, as noted above, confidence-building measures that could be used to increase transparency.

MOVE TWO SCENARIO

Despite the promising negotiations conducted during move one of the game, sponsors desired to examine a new series of issues in move two. Therefore, they informed participants that the second move was not a continuation of the morning session, but rather a new scenario based on the assumption that diplomatic efforts had not resolved the crisis. At the beginning of move two, the announcement was made that Pakistan had launched a nuclear attack against India. Several offensives and counteroffensives preceded this nuclear crisis. Outraged by India’s unrepentant celebrations over the success of Operation Resolute Sword, the Pakistani high command seized the opportunity to surprise and punish Indian forces involved by launching Operation Resolute Shield in the region east and south of Lahore. During a two-day battle, Pakistani forces managed to push about 50 kilometers into Indian territory. An Indian counteroffensive managed to repulse the Pakistani thrust. Engaged forces were joined by a large number of redeployed Indian troops and together they launched an attack toward the Pakistani border.

Despite the promising negotiations conducted during move one of the game, sponsors desired to examine a new series of issues in move two. Therefore, they informed participants that the second move was not a continuation of the morning session, but rather a new scenario based on the assumption that diplomatic efforts had not resolved the crisis. At the beginning of move two, the announcement was made that Pakistan had launched a nuclear attack against India. Several offensives and counteroffensives preceded this nuclear crisis. Outraged by India’s unrepentant celebrations over the success of Operation Resolute Sword, the Pakistani high command seized the opportunity to surprise and punish Indian forces involved by launching Operation Resolute Shield in the region east and south of Lahore. During a two-day battle, Pakistani forces managed to push about 50 kilometers into Indian territory. An Indian counteroffensive managed to repulse the Pakistani thrust. Engaged forces were joined by a large number of redeployed Indian troops and together they launched an attack toward the Pakistani border.

The attacks were enormously successful. Pakistani forces in the north were defeated and Indian forces moved quickly across the Thar Desert toward the Indus River. Fearing that India was about to sever the country in two, cutting off Islamabad’s economic lifeblood to the south, the Pakistani high command ordered a barrage of missile strikes, including four nuclear-tipped weapons. Three 20-kiloton tactical nuclear weapons were aimed at halting invading Indian forces on the border and the fourth used against the supporting rail hub in Jodhpur. The attacks succeeded in stalling the Indian advance and destroying the rail hub. Exact casualty figures were not available, but they were estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.

Move Two ¾

Initial Reactions

In a tersely worded statement, India noted that defensive precautions had been taken following Pakistan’s unwarranted nuclear attack and government leaders were being relocated to alternative command sites. Since communications between New York and New Delhi were impossible, India withdrew its representative from the Security Council and noted that the time for diplomatic efforts had passed. India gave no indication of what course it might steer in reaction to these events.

Pakistan expressed its sincere regret that this catastrophe had to occur, but explained that its actions were purely defensive and the only course left to it considering Indian aggression. Pakistan pointed out that it had used only tactical nuclear weapons against strictly military targets ¾

avoiding deliberately targeting population centers. It hoped Indian leadership would see the futility of its aggression and seek peace. Pakistan reiterated that it would not accept any country’s hegemony in the region and threatened to use nuclear weapons against Indian cities if India did not cease its military actions.

Russia decried Pakistan’s actions and indicated that it was sending humanitarian assistance and decontamination equipment to India. Russia called for the immediate denuclearization of Pakistan and India as well as a renewed effort by the international community to enforce the non-proliferation regime. It called on India to refrain from a nuclear counterattack but offered decontamination assistance to Pakistan should one occur. Russia put the U.S. on notice that it had dispersed it strategic forces and was suspending the START inspection regime until the crisis was over.

China insisted that the international community had to bear some responsibility for the Pakistani attack since it had neglected to ensure a military balance in the region. It urged the international community to begin at once to restore this balance. Although China did not justify Pakistan’s use of nuclear weapons, it did note that Pakistan had only used tactical, counterforce weapons [a point some countries said was inconsequential]. China called upon India to desist from pursuing retaliation in kind and noted that the two most important requirements were to restore order and begin decontamination.

The United States insisted that the UN Security Council had an inescapable obligation to get involved in this crisis. It strongly condemned Pakistan's actions and indicated that it would help search for an appropriate way to punish the Pakistani government for its outrageous conduct.

Iran indicated that Pakistan's actions had caused many regrets in the region including in Iran. Iran indicated that India should have done more to prevent the unfortunate turn of events and cautioned India that if it retaliated it would endanger both global peace and the environment.

Most other members of the Security Council condemned Pakistan for using nuclear weapons and were eager to stop the situation from escalating. Canada once again called upon the Secretary-General to take the lead. The President of the Security Council pressed for immediate action, believing that any hesitation in responding would only make matters worse. Finland agreed with China that the international community, particularly the great powers, must be assigned a share of the blame in this situation. It asked about indications and warnings that the great powers might have had, and wondered why they did not intervene if they had any. Finland also offered to get the European Union (EU) involved in the relief effort. Canada decried the fact that its earlier proposal for IAEA involvement had not been implemented since it might have prevented the use of nuclear weapons. The Philippines indicated that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) would also collaborate on the matter.

At this point the Security Council once again adjourned and members were free to join in informal collaboration. The Permanent Five, along with the President of the Security of the Council and Secretary-General, went into a closed session. They negotiated with India and Pakistan separately. Several other countries, led by Canada, Australia, and Japan, met to consider ideas they could present to the Permanent Five.

Move Two ¾

Negotiations

During their deliberations, the Permanent Five decided that they would not intervene militarily to stop the crisis ¾

fearing that such intervention would only raise the stakes, maybe even leading to World War III. They did consider putting sanctions and embargoes in place against Pakistan. China insisted that any international actions be evenhandedly implemented. The President of the Security Council urged the Permanent Five to station a token number of people on the ground to serve as a firebreak against further nuclear exchanges.

Pakistan’s reaction to the Permanent Five’s decision not to intervene was a mixture of disbelief and dismay. Pakistan indicated that the Permanent Five were both deluded and self-centered if they thought their non-intervention could prevent World War III. He noted that this was World War III and that more people were involved in this conflict than had been in all of World War II whether or not the major powers got involved.

The President of the Security Council noted that it would not be in the best interests of the international community to take sides in this conflict. He also indicated that events appeared to be moving too fast for the Security Council to act. The United States agreed that letting history decide who to blame was the best course to follow. The U.S. averred, however, that only the belligerents could stop the fighting. If they were ready to do that, then the Security Council did have a role to play. When asked what it would take to deter India from responding, India listed four conditions: 1) complete demilitarization of Pakistan and destruction of its nuclear, and other mass destruction, weapons; 2) imposition of wide-ranging, comprehensive sanctions against Pakistan until this was accomplished; 3) a legally binding and unequivocal commitment by all nuclear powers to engage in a process leading to the complete elimination of nuclear weapons and adoption of a universal renunciation of the use of nuclear weapons; and 4) compensation and rebuilding of areas in India that were devastated by the nuclear attack.

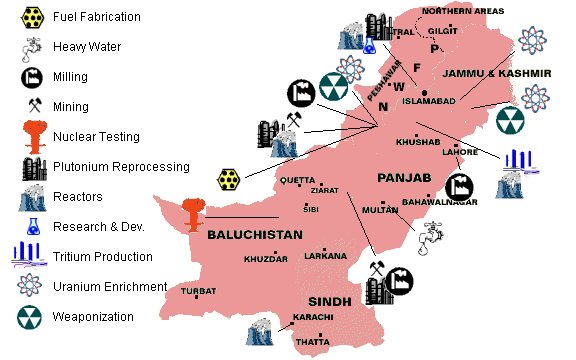

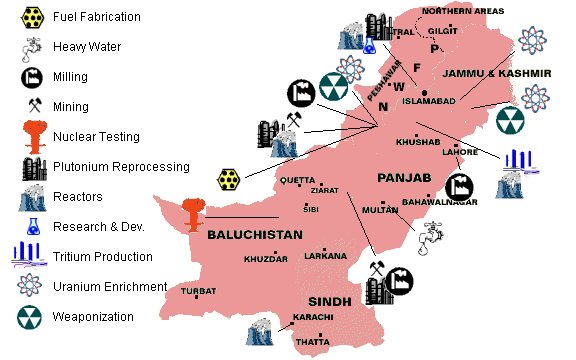

At this point, discussions were interrupted and participants were informed that India had opted to launch twelve nuclear weapons against Pakistan’s nuclear and command infrastructure, including facilities around Islamabad. As the accompanying figure illustrates, many of Pakistan's nuclear-related facilities are close to populated areas (also see Figure 4). As a result, Indian nuclear attacks were estimated to have caused casualties reaching into the millions.

Following the Indian attack, players expressed regret over India's actions and clearly struggled with how to proceed. The President of the Security Council recommended that the open session adjourn once again so that the Permanent Five and other groups could consult. China wanted the record to show that this situation was initiated by Indian aggression and, as opposed to Pakistan's tactical nuclear weapons attack, its attacks were strategic in nature, had eliminated Pakistan's government and killed large numbers of innocent people. The United States laid blame for the catastrophe at the doorsteps of the Indian and Pakistani governments and questioned whether they were ready to stop the carnage. The Secretary-General, whom the Canadians had been trying to spur into taking charge, noted that this crisis was beyond the secretariat's ability to control ¾

"This is not Rwanda." At that point, participants adjourned for consultations.

Move Two ¾

Outcomes

When the Security Council reconvened, the Permanent Five, who had negotiated separately with India and Pakistan, outlined a proposal for ending the crisis that included the following points.

- Immediate cessation of military activities.

- Renunciation and elimination of nuclear capabilities by both countries.

- A return to the status quo ante in Kashmir.

- International security guarantees for both India and Pakistan.

Figure 4. Pakistani and Indian nuclear attacks

During its discussions with the Permanent Five, India noted that its nuclear program was oriented toward more countries than just Pakistan (for example, China). Pakistan, on the other hand, indicated its nuclear program was directly related to India's. As to other demands, Pakistan noted that the Indian attacks had so disrupted its infrastructure that it could not guarantee total control over its forces. It was concerned that a rogue or uninformed unit might inadvertently reignite conflict. India pledged not to respond beyond self-defense to such isolated incidents. One controversial aspect of this proposal was the offer of Permanent Five security guarantees to both India and Pakistan if they would renounce their nuclear programs. Many participants believed that such guarantees would be difficult to "sell back home," and just as difficult to implement. The United States shared that assessment, but explained that it had gone along in the interest of time. Although the Security Council approved the proposal by acclamation, time did not permit debate about its merits or shortcomings.

As during move one, Canada, Australia, and Japan also consulted and prepared an alternative proposal they had hoped to present to the Permanent Five. Many of their recommendations mirrored those of the Permanent Five (such as an immediate cessation of military operations and a return to 1 August positions). They presented several recommendations, however, that were not contained in the adopted resolution. The most debated recommendation was for a large international interposition force. They believed that such a force would provide a face-saving mechanism to allow both sides to disengage more easily and they regretted the fact that the Permanent Five dismissed that option. Australia, Canada, and Japan also recommended the establishment of a fact-finding mission and adoption of measures to deescalate tensions that fell short of total denuclearization (including the decoupling of warheads from delivery systems). Singapore welcomed calls for the denunciation of nuclear weapons and posited that it would be a good time for all nuclear powers to so do. Japan agreed. The U.S. countered that while some reflection on the utility of nuclear weapons would likely take place following an event like this, such reflection would probably not change positions or policy.

OUT OF ROLE DISCUSSIONS

The concluding portion of the game provided participants the opportunity to explain the motivating factors behind their role-playing and assess the implications of the scenario. In the cases of India and Pakistan, the game sponsor noted that their positions wove free play diplomacy with game artificialities. The players explained their views of the simulation as follows:

Pakistan attempted to assume the moral high ground because it was in a militarily weaker position than India and because such a stance would have played well domestically. Considering the security imbalance, Pakistan has "pushed its luck" in its relationship with India and would have quickly sued for a cease-fire during move one. Pakistan also attempted, as it traditionally has, to draw outside powers (especially, China, Iran, and, the United States) to its cause. Pakistan took an alarmist position during move one in order to generate a sense of urgency in the international community. It believed that the lack of international action could have pushed Pakistani hawks toward nuclear confrontation.

India acknowledged that possessing nuclear weapons places a special responsibility on it as well as Pakistan. For that reason, India and Pakistan would have worked very hard to reach a peaceful settlement. India pointed out, in fact, that since the public tests of nuclear weapons, India and Pakistan have raised their negotiations to a new level. During move two, as unthinkable as nuclear conflict was, there would have been only one type of response to the Pakistani nuclear attack and that is what took place.

Canada wanted to get as many people involved on the ground in the troubled areas as possible, believing that they would deter further violence. Canada found it disturbing that members of the Permanent Five undermined adoption of the move one resolution, even though its language had been accepted by the two belligerents. [The United States indicated that without having some CBMs included in the resolution's language it could not commit troops. The U.S. acknowledged that disagreement was probably more of a game artifact than a real obstacle, because it most likely would have been resolved had more time been allotted for negotiations.]

Japan indicated that three principles guided its position: negotiate before intervening, pursue implementation of an immediate cease-fire, and push for de-escalation and renunciation of nuclear weapons. Japan pointed out that once nuclear weapons were used, the international community realized how limited its options were; therefore, preventing the use of nuclear weapons was the only reasonable course to follow. Even though it has significant economic ties to the area, Japan pointed out that it was constitutionally limited as to how involved it could become.

The Philippines noted that it had a significant Muslim population and was therefore sensitive to any situation involving members of that faith. On the other hand, there was also an influential Indian minority in the Philippines. Since the Philippines had little influence in the UN, it looked to ASEAN to generate leverage in this situation (although it assumed that ASEAN could generate limited influence). As a result, the Philippines attempted to collaborate with its more powerful friends to see how it could support their positions. The Philippines believed that the UN would have minimal leverage during a crisis like this, although had more Non-Aligned Movement and Group of 77 countries been represented, the interests of smaller nations might have played more prominently. It also recommended exploring leverage that could be brought to bear by global and regional financial institutions.

The Philippines noted that it had a significant Muslim population and was therefore sensitive to any situation involving members of that faith. On the other hand, there was also an influential Indian minority in the Philippines. Since the Philippines had little influence in the UN, it looked to ASEAN to generate leverage in this situation (although it assumed that ASEAN could generate limited influence). As a result, the Philippines attempted to collaborate with its more powerful friends to see how it could support their positions. The Philippines believed that the UN would have minimal leverage during a crisis like this, although had more Non-Aligned Movement and Group of 77 countries been represented, the interests of smaller nations might have played more prominently. It also recommended exploring leverage that could be brought to bear by global and regional financial institutions.

Russia played its role assuming that a moderate, nationalist, authoritarian government was in place. Since India would be seen as a natural and continuing ally, Russia was willing to offer it wide-ranging security guarantees (especially if India was forced to denuclearize). By steering a prudent course, Russia believed it could strengthen ties with India and forge new ones with Pakistan (ties that could be used as leverage in its continuing tension with Afghanistan). Because Russia was not strong enough to create opportunities of its own, it looked for exploitable opportunities created by others. It was willing to follow the U.S. lead in the game because U.S. objectives were acceptable and being pursued through the UN. Had circumstances required it, Russia was willing to break down the nuclear proliferation regime by renouncing the Non-proliferation Treaty because it was unhappy with the current international system. Russia stated that it is on the verge of breaking down and is not unwilling to see the international system go down with it.

Peru indicated that the Latin American perspective was important for the game because the Latin American nuclear free zone had demonstrated that a regional approach to denuclearization could work. Peru wanted quick action (believing that doing something is better than doing nothing). "You shoot quickly and often, hoping that one of the bullets hits the target." Hence, acting as President of the Security Council, Peru pressed for an early resolution, and was disappointed when that didn't happen. Peru said that the Permanent Five were too cautious. "You should make several quick decisions rather than trying to write the perfect resolution." Peru also noted that if diplomatic actors don’t act, non-diplomats will. "You have to make decisions. You need a commitment to the international system to make it successful."

Singapore said it felt powerless to influence the situation and, therefore, remained silent during most of the discussion. As a matter of principle, it disliked intervention, preferring to see belligerents work out their own problems. However, intervention in this case appeared prudent. It did note that the Permanent Five appeared to ignore the principle of management that argues for getting others to buy into or take ownership of an idea (in this case, a UN resolution). Singapore said the P5 did not solicit the ideas of others, but expected them to bend to the P5's will.

Finland remained neutral during the game. This meant supporting humanitarian assistance efforts and taking the position that negotiations represented the best path to conflict resolution.

Iran tried to play an evenhanded diplomatic role without abandoning its historical and religious links with Pakistan. In a real crisis, Iran said it would have worked with the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC) to put pressure on the Permanent Five countries to act to prevent the killing of Muslims. Iran recognized that this would probably have resulted in generating little leverage. Iran indicated that it would have preferred regional organizations ¾

working under the supervision of the United Nations ¾

deal with the problem, but understood that in this scenario such organizations would have had insufficient power to act. Despite its disappointment with Pakistan's use of nuclear weapons, Iran did not abandon its support for Pakistan because it is a Muslim state.

The United States played its role consistent with current foreign policy positions, except when it was willing to send in troops and to extend security guarantees at the end of move two. The key U.S. player acknowledged during the out of role discussion that neither of those ideas would easily pass Congress. The U.S. indicated that the principal lesson to be learned is that it is easier to prevent a nuclear war than to deal with one once it has begun. The U.S. aim was to prevent a nuclear exchange and, if it could not accomplish that, to deter escalation (both between belligerents and among the great powers). Maintaining a Permanent Five consensus was critical to this effort, which meant that most of its time was spent negotiating with other P5 members.

China took the long view in playing its role. China's two primary long-term concerns were Taiwan and Tibet (with Taiwan being the higher priority). All other interests were secondary. China acknowledged in retrospect that it could have created a diversion on the China-India border in support of Pakistan during move one that might have lessened Pakistan's sense of isolation. The India problem was inextricably tied to the Tibet problem, since Tibetan independence activists would have likely taken advantage of any crisis to side with India. Therefore, China’s strategy was to maintain India's focus on Pakistan and prevent an Indian offensive against China.

The United Kingdom indicated that because it had such large Pakistani and Indian populations it could not realistically take sides in this scenario. It averred that in such circumstances there was little leverage to be brought to bear on either side, and that the crisis demonstrated the consequences of letting contested issues fester without efforts to resolve them. Nevertheless, its aim was to prevent conflict and the UK believed an observer force in move one (such as recommended by Canada) could have helped. The U.K. agreed with the U.S. that the resolution offered during the morning session would have been successfully worked out had time permitted discussion to continue. It went along with the U.S. because it believed the situation required a coherent Permanent Five approach. The U.K. did not agree with its Commonwealth friends that intervention during move two would have been either successful or wise.

France said it tried to play the role of honest broker during the crisis. It supported strengthening air and ballistic missile defenses in South Asia, establishing a fact-finding mission, and implementing new confidence-building measures. Its goal during move one was to prevent further escalation. During move two, France's goal was to prevent the conflict from spilling over to other states in the region. It believed that the Permanent Five could have exploited the initial shock created by the nuclear exchange to begin a crisis management process. It supported economic sanctions but believed that more immediate measures were necessary for dealing with the crisis at hand. Hence, in contrast to its position in move one, France supported a UN interposition force armed with air and ballistic missile defenses, and the immediate provision of humanitarian assistance. France questioned the viability of security guarantees made by the Permanent Five.

France said it tried to play the role of honest broker during the crisis. It supported strengthening air and ballistic missile defenses in South Asia, establishing a fact-finding mission, and implementing new confidence-building measures. Its goal during move one was to prevent further escalation. During move two, France's goal was to prevent the conflict from spilling over to other states in the region. It believed that the Permanent Five could have exploited the initial shock created by the nuclear exchange to begin a crisis management process. It supported economic sanctions but believed that more immediate measures were necessary for dealing with the crisis at hand. Hence, in contrast to its position in move one, France supported a UN interposition force armed with air and ballistic missile defenses, and the immediate provision of humanitarian assistance. France questioned the viability of security guarantees made by the Permanent Five.

Australia attempted to collaborate with non-permanent members of the Security Council and decried the fact that it had not undertaken to engage more countries earlier in the game in order to achieve more leverage in the debate. It recommended that the Permanent Five seek a wider number of views during their consultations. Australia believed that it, as well as some other countries, could have diplomatically punched above its weight, especially in this area of the globe. Australia noted that new perspectives are often quite valuable.

Australia attempted to collaborate with non-permanent members of the Security Council and decried the fact that it had not undertaken to engage more countries earlier in the game in order to achieve more leverage in the debate. It recommended that the Permanent Five seek a wider number of views during their consultations. Australia believed that it, as well as some other countries, could have diplomatically punched above its weight, especially in this area of the globe. Australia noted that new perspectives are often quite valuable.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

International organizations are likely to be ineffective in addressing a nuclear crisis in South Asia.

Although some states thought it wise to make the United Nations (particularly the Secretary-General) the primary instrument of mediation during both moves, it was generally felt that the United Nations had neither the leverage nor the time to deal with this kind of crisis. By default, resolution of the crisis fell into the laps of the Permanent Five, who would probably consult within, but act outside, the UN framework. The risk of veto in a United Nations setting was very real since each belligerent had its advocate. A coalition of the willing, with or without UN sanction, appeared to have a much greater chance of acting in a timely fashion. Pakistan wanted and needed a timely response from the international community. Without that, its sense of isolation, vulnerability, and desperation led to dire miscalculation. India specifically commented that only the rapid deployment of an interposition force involving forces from the Permanent Five could have deterred it from retaliating against Pakistan.

For the foreseeable future, "managed tension" will be the norm.

In South Asia, there remains significant intransigence on both sides. The perception is that the situation, especially in Kashmir, is a zero sum game in which a gain for one side is a loss for the other. This all or nothing mindset provides either side with little maneuvering space. One participant went so far as to suggest the solution was an independent Kashmir. During the game, there was insufficient time available to address longer-term solutions to the underlying causes of the crisis. Although it was recommended that the international community should marshal its forces and tackle this challenge, participants noted that many factors worked against international efforts. They included the asymmetries between Pakistan and India, the distances involved, the intractability of the two sides, and India's opposition to outside involvement. Pakistan noted that Kashmir was only one of a number of issues affecting the India-Pakistan relationship. Most participants, however, believed that the introduction of nuclear weapons has added a new dimension to the situation and that resolving the tension over Kashmir is the key to lasting peace.

Historic ties shape perspectives.

Past conflicts between India and Pakistan were not the only events that colored game play. Past relations between India and China and other historical relationships (such as Russia's long-time support for India) also played a role. It was noted that had the makeup of the game’s Security Council more closely mirrored its actual membership, India would have been able to generate greater support from members of the Group of 77 while Pakistan would have looked to the Organization of Islamic Countries for assistance.

Conventional force confidence-building measures need to be complemented by nuclear CBMs.

The greatest concern expressed during discussions, and the one examined during move two, was the exchange of nuclear weapons resulting from either accident or miscalculation. India and Pakistan claimed the risk is much higher in the short term because they anticipate, in the long-term, putting in place mechanisms for dealing with accidents and misperceptions. Participants pointed out that, because of the distances involved, the mechanisms used by the U.S. and Soviet Union during the Cold War had the luxury of time that is not present on the sub-continent. Finding mechanisms that can react fast enough to prevent escalation could prove problematic.

Nuclear weapons provide states with enhanced negotiating leverage.

The world’s attention was more rapidly captured by the crisis because of the chance that nuclear weapons could be threatened and used. Pakistan held a wild card as far as the international community was concerned because its weaker position vis-à-vis India increased its temptation to both threaten and use nuclear weapons when attacked. Pakistan benefited most from this phenomenon because it desired broader international involvement. Once Pakistan used nuclear weapons, its leverage was quickly lost and it found itself in a morally weakened position. Prior to the exchange of nuclear weapons, states realized that they had to deal evenhandedly with India and Pakistan. India, however, was not looking for evenhandedness, but equality, in its dealings with other nuclear powers.

Conflicting views concerning nuclear weapons will continue.

Although several states have abandoned their nuclear programs, notably South Africa, Argentina, and Brazil, India made it clear that it believes the possession of nuclear weapons is one of the entrance requirements to great power status. India believes it deserves the same international status as China, and has pursued a nuclear option ever since China exploded its first bomb. India also understands why Pakistan feels it must match India's nuclear program. The Permanent Five's diplomatic dominance in addressing this crisis served to underscore India's commitment to nuclear weapons.

Post-nuclear exchange options are extremely limited.

Attendees found that both military and other options were limited once nuclear weapons had been used. Options identified included: provision of technical assistance to enhance transparency; non-combatant evacuation operations; humanitarian assistance; consequence management (such as decontamination operations); emplacement of interposition forces; deployment of passive and active defensive measures (e.g., air and missile defenses); and various financial incentives (or denial thereof).

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Pursue sources of leverage and be willing to use it.

Participants struggled to find ways to influence the belligerents, discovering that, if leverage did not exist prior to the crisis, it could not be generated after it began. Leverage is normally generated through positive incentives (e.g., trade agreements, international loans, foreign aid, etc.). During both moves, sanctions and embargoes were raised as options, but they were only effective options when used by those having good relations with the belligerents. (The sanctions put in place as a result of 1998 nuclear tests [see Appendix E] had been lifted as part of the scenario.) Those countries possessing the greatest leverage going into the crisis ¾

China, Russia, and Iran ¾

were also the most reluctant to use it. Many players questioned the effectiveness of sanctions, indicating that the international community had yet to learn how to target offending governments or leaders without causing undue suffering among the population.

Pre-crisis sanctions weaken, rather than strengthen, international leverage

Players pointed out that countries supporting long-term sanctions decreased, rather than strengthened, sources of leverage. This was true for three reasons. First, sanctioning countries were placed in an adversarial position vis-à-vis sanctioned states, and all but coercive forms of influence were lost. Second, the longer sanctions were in place the greater the number of coping mechanisms that could be put in place by the target country. Finally, as mentioned above, coping mechanisms normally benefit the governing elite while the general population suffers the brunt of the sanctions. Although some players doubted the efficacy of any sanctions, others suggested that the timing of sanctions was critical and indicated that it was a tool that could be overplayed.

Leverage weakens as a crisis escalates.

As the crisis deepened, even those countries possessing the greatest leverage (China, Russia, and Iran) discovered that their influence waned. Once events were set in motion, they followed a logic and sequence that became increasingly immune to outside pressure. The suggestion of applying sanctions only tended to reinforce the growing isolation felt by India and Pakistan and strengthened their determination that they must be capable of acting alone.

Terrorism can precipitate interstate conflict.

Several participants opined that cross-border terrorism in South Asia could plausibly precipitate war. It was imperative, therefore, that terrorism be addressed before it got out of hand. The trigger event in move one ¾

the aircraft incident in which high-ranking Indian ministers were killed ¾

demanded a response. That said, India's unilateral counteroffensive escalated the game crisis. This prompted some participants to recommend a broad-based approach to counter terrorism.

The International community should be more proactive.

Participants asserted that the awful events presented during this exercise underscored the importance of dealing preemptively with situations that could lead to nuclear war. Some participants suggested that deterrence mechanisms needed to be identified. Others recommended that the international community identify both "carrots and sticks" that could be used to influence nations in crisis. Most participants understood, but lamented, the fact that the international community deals with most problems reactively, if at all. In fact, Peru recommended that the UN adopt a new flag: "An azure field, containing a golden ostrich, with its head stuck in silver sand."

Non-proliferation and comprehensive test ban treaties are more likely to delay than halt the of spread nuclear weapons.

As noted above, countries pursue nuclear weapons for a variety of reasons they deem essential to their national security. International pressure is unlikely to dissuade them from their course. This means that the international community, particularly the Permanent Five, needs to reexamine how it deals with these states. Excluding responsible nuclear powers from the "nuclear club" may no longer be the most effective course to follow. Such an approach, however, would still beg the question of how to deal with rogue states pursuing a nuclear option. Nuclear powers can expect continuing, if not increasing, pressure from the rest of world to engage seriously in denuclearization talks.

Unilateral options are unlikely to work.

Even though participants recognized that the United Nations is impotent to deal with a major regional conflict, they were only willing to follow the U.S. lead because it was acting within the UN structure. Several states asserted that they would have objected to any unilateral approach. This was particularly clear in the case of Russia and, possibly, China. Considering the fact that these two states are better placed to influence India and Pakistan respectively, having their support for any U.S. plan of action was critical. The point was also made that the U.S. would find it impossible to contribute to an interposition force unless India and Pakistan requested it.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

The primary purpose of this game was to explore international approaches for dealing with crises involving the threat and use of nuclear weapons. Participants from India and Pakistan were much more sanguine that their countries could avoid nuclear conflict than were most other participants. All agreed that miscalculation and accident were the most likely paths leading to nuclear war. Miscalculation was at the heart of the game's second move and most players were sobered by the results.

Both wishful thinking and concrete proposals emerged during the game. Players fell into three groups: moralists, pragmatists, and fatalists. The moralists assumed the high ground and recommended global elimination of nuclear weapons. The pragmatists urged nuclear stockpile reductions, confidence-building measures, and continuing efforts to slow the proliferation of nuclear technologies. They recognized that getting the nuclear genie back in the bottle was nigh impossible. The fatalists recommended letting the belligerents fight it out and suffer the full consequences of their folly.

To a person, participants brought an impressive level of professionalism and seriousness to their roles. Time restrictions precluded participants from exploring a number of promising areas of influence, particularly the economic arena, which will be addressed in future events. This game highlighted the understanding that bilateral or regional sources of tension quickly become international concerns when nuclear weapons are introduced. It also underscored the fact that searching for solutions "on the day" is an ineffective, and possibly catastrophic, approach.

APPENDIX A: INDIA/PAKISTAN: MILITARY ASSUMPTIONS IN 2003

| |

Pakistan |

India |

|

Total Military Personnel |

587,000 active

526,000 reserve |

1,145,000 active

1,005,000 reserve |

|

Army |

|

|

|

Army Troops |

520,000 |

980,000 |

|

Tanks |

2,350 |

4,500 |

|

Artillery |

1,566 towed

240 self-propelled |

4,075 towed

180 self-propelled |

|

Light Aircraft |

200 |

NA |

|

Air Force |

|

|

|

Combat Aircraft |

503 |

900 |

|

Transport Aircraft |

28 |

230 |

|

Helicopters |

NA |

60 |

|

Air Force Personnel |

45,000 |

110,000 |

|

Navy |

|

|

|

Surface Ships

Destoyers

Frigates |

11

3

8 |

24

6

18 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

- |

1 |

|

Submarines |

9 |

17 |

|

Nuclear Weapons |

50 to 75 warheads (all 10-

20 kiloton yield) |

75 to 100 warheads (all 10-

20 kiloton yield) |

|

Ballistic Missiles |

Pakistan |

|

India |

|

| |

Type |

Number |

Type |

Number |

| |

Ababeel SRBM |

60 [20 TELs] |

Prithvi I SRBM |

60 [8 TELs] |

| |

Ghauri MRBM |

15 [3 TELs] |

Prithvi II |

20 [2 TELs] |

| |

Shaheen I |

5 [2 TELs] |

Agni |

10-

15 |

| |

Shaheen II |

2 |

|

|

APPENDIX B: INDIA -

PAKISTAN CHRONOLOGY

INDIA -

PAKISTAN CHRONOLOGY

~800 Muslim invasions of current day Pakistan begin.

~1000 Muslim invasions of current day India begin.

1498 Vasco da Gama voyages to India opening up subcontinent to Western Europe ¾

mainly Holland, Portugal, England, and France.

~1700 Muslim Mughal empire encompasses large part of India. Hindu Marathas rise up and control another large section of India.

1709 British East India Company established.

1757 British defeat combined Mughal -

French force.

1773 Regulating Act of 1773 regulates activities of British East India Company in India.

1784 India Act of 1784 (sponsored by Pitt) provides for a joint government for India comprised of the British East India Company (represented by the Directors of the company), and the British Crown (represented by the Board of Control).

1786 Lord Cornwallis becomes Governor General of British East India Company, thereby becoming de facto ruler of India.

1818 British defeat Marathas (Hindu) force.

1849 British defeat Sikhs and thereby control virtually all of India.

1857 - 58 Indian Mutiny against British East India Company. Following British victory, British government takes direct control of India.

1885 Indian National Congress, dominated by Hindus, is formed as Indian nationalist sentiments begin to crystallize.

1906 All India Muslim League formed ¾

primarily out of fear that Hindu dominated Indian National Congress will subordinate Muslim interests.

1914 - 18 Congress and Muslim League support British in WWI

1918 Following WWI, Muslim League begins to oppose British due to partition of Ottoman Empire.

1919 British pass "Government of India Act of 1919" granting limited self rule to India.

1920’s Indian National Congress sanctions acts of civil disobedience against British Rule. Mohandas Gandhi emerges as leader of nationalistic movement.

1930 Gandhi leads March to the Sea to protest British tax on salt.

1934 Mohammed Ali Jinnah becomes leader of Muslim League.

1935 British pass "Government of India Act of 1935" expanding power of elected national and provincial legislatures.

1940 Muslim League endorses partition of India into separate Hindu and Muslim states. The name "Pakistan" (meaning Land of the Pure) is widely adopted as the name for the proposed Muslim state.

1939 - 45 India supports Britain during World War II.

1947 (March) British Lord Mountbatten becomes last Viceroy of India.

(July) British pass "India Independence Act."

(July/August) Ten million Indians move to "safe" areas in India and Pakistan. Nearly 1,000,000 are killed, including large numbers of Sikhs.

(August 14) Indian Subcontinent formally partitioned into India and Pakistan. Pakistan, primarily Muslim, becomes an independent dominion of the British Commonwealth of Nations. It consists of East and West Pakistan, which have no contiguous borders and are separated by a thousand miles at their closest points. Jinnah becomes first Governor General of Pakistan.

(August 15). India becomes an independent nation. Jawaharlal Nehru (Congress Party) becomes first Prime Minister of India. India is primarily Hindu.

(October) First undeclared war between India and Pakistan flares up over Kashmir. British aid India with air power. Results in partition of Kashmir into Pakistani controlled Azad Kashmir and Indian controlled Jammu and Kashmir.

1948 (January) Mohandas Gandhi assassinated.

(September 11) Mohammed Ali Jinnah dies. Liaquat Ali Khan becomes Governor General of Pakistan.

India Department of Atomic Energy created.

1950 (January 26) India’s constitution goes into effect.

1951 Liaquat Ali Khan assassinated, Khwaja Nazimuddin becomes leader of Pakistan.

1953 Mohammed Ali Bogra becomes leader of Pakistan.

1954 India signs friendship treaty with China.

1955 Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission set up to promote peaceful uses of Atomic Energy.

1956 Pakistan becomes a republic. Major General Iskander Mirza becomes first president.

First Indian Nuclear Research Center set up at Aspara.

1961 India forcibly occupies Portuguese enclaves of Goa, Daman, and Diu.

1962 India -

China border dispute over Assam in Northeast India. India badly beaten. Chinese occupy part of Kashmir and claim more land in Northeast India. Dispute remains unresolved.

India’s first heavy water plant established.

1963 India’s 40 MW Cirus nuclear research reactor goes on stream.

1964 (May 27) Nehru dies. Lal Bahadur Shastri (Congress Party) becomes Prime Minister.

1965 Second India -

Pakistan War over Kashmir.

1966 Lal Bahadur Shastri dies. Indira Gandhi (Congress Party and daughter of Nehru) becomes Prime Minister.

1967 Uranium Corporation of India, Ltd. formed for mining and milling uranium ore.

1969 Tarapur Atomic Power Plant begins commercial operation near Bombay.

1970 Cyclone and tsunami strike East Pakistan killing 266,000. East Pakistanis claim relief is slow to come from seat of federal government in West Pakistan.

1971 (March 26) East Pakistan secedes from Pakistan and forms new nation of Bangladesh. Civil War erupts between East and West Pakistan.

Third India -

Pakistan war erupts as India supports East Pakistani rebels.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto becomes Prime Minister of Pakistan.

Indira Gandhi Center for Atomic Research set up in Kalpakkam.

1972 Pakistan starts up first nuclear power station ¾

Karachi Nuclear power Plant (KANUPP) in Karachi with Canadian help.

India commissions Purnima Research Reactor.

1973 Pakistan adopts new constitution with a president as head of state and a Prime Minister as chief executive. Bhutto becomes Prime Minister and Chaudhri Gazal Elahi becomes President.

Unit 1 of India’s Rajasthan Atomic Power Station begins commercial operation.

1974 Prime Minister Ali Bhutto vows Pakistan would "eat grass" if necessary to go nuclear after India explodes its first nuclear device.

(May 18) India conducts first underground nuclear test at Pokhran in desert state of Rajasthan.

1975 Indian High Court finds Indira Gandhi guilty of violating election laws and bans her from politics for six years. In response, she declares a state of emergency and assumes dictatorial powers, restricting many freedoms.

1976 France agrees to sell nuclear reprocessing plant to Pakistan that would allow Pakistan to extract weapons grade plutonium.

Canada ends nuclear ties with Pakistan, cutting supplies for the KANUPP plant which it helped build.

Pakistan sets up Kahuta Research Lab to establish uranium enrichment capability..

1977 Indira Gandhi ends period of emergency. Long overdue free elections are allowed and Gandhi loses and Morarji Desai (Janata Party) becomes Prime Minister.

India’s heavy water plant at Baroda set up.

Pakistani Prime Minister Ali Bhutto overthrown by Gen. Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq. Zia declares martial law.

1978 Indian Congress party splits into Congress and Congress (I) [ "I" for "Indira"] parties.

India sets up heavy water plant at Tuticorin.

Zia declares himself president of Pakistan. He also retains title of Prime Minister.

Under pressure from U.S., France cancels 1976 reprocessing deal with Pakistan.

1979 Charan Singh (Janata party) becomes Prime Minister of India.

(April) U.S. cuts off all military and fresh economic aid to Pakistan refusing to accept assurances from Islamabad that its nuclear program is peaceful.

(August) Pakistan intensifies security around its nuclear establishments, moving ground to air missiles near the Kahuta plant.

Ali Bhutto executed.

1980 Indira Gandhi (Congress [I] party) reelected Prime Minister of India.

(August) Pakistan says it can fabricate nuclear fuel indigenously.

1981 Unit-2 of India’s Rajasthan Atomic Power Station begins operation.

1980’s Sikhs seek to establish independent state in Punjab.

1983 Indian Atomic Energy Regulatory Board set up to regulate domestic nuclear power plants.

1984 (June) Indira Gandhi orders attack on Golden Temple of Amritsar, Sikhs’ holiest shrine, killing 450.

Unit 1 of India’s Madras Atomic Power Station begins operation.

India’s Purnima-2 Research Reactor commissioned.

(November) Indira Gandhi assassinated by Sikh bodyguards. Her son, Rajiv Gandhi (Congress [I]), becomes Prime Minister.

(December) 2,500 die and thousands injured in the world’s worst industrial accident when a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal emits poisonous gas.

1985 (February 24) Pakistani President Zia says Pakistan has produced enriched uranium, but says it is for purely peaceful purposes.

Zia ends martial law and allows election of new parliament.

1987 Indian troops sent to Sri Lanka as a peacekeeping force following an armed separatist struggle by Tamil Tigers. India loses 1,140 men when the Tigers turn against the peacekeepers. Indian troops withdraw in 1990.

1988 (August) Pakistani General Zia dies in a plane crash.

(November) Benazir Bhutto (daughter of Ali Bhutto) is elected Prime Minister - the first woman to head an elected government in a Muslim nation.

(December 31) India and Pakistan sign agreement prohibiting attack on each other’s nuclear installations.

1989 Moselm guerrillas launch an armed separatist struggle in Kashmir.

(December 1) V. P. Singh (Janata Dal) becomes Prime Minister of India upon resignation of Rajiv Gandhi. Gandhi remains head of Congress (I) party.

1990 (August) Pakistani President Ishaq Khan accuses Prime Minister Bhutto’s government of corruption and removes her from office.

(November) Nawaz Sharif becomes Prime Minister of Pakistan.

(November 10). Chandra Sekhar (Janata Dal) becomes Prime Minister of India.

1991 (January 27) Pakistan and India ratify 1988 agreement banning attacks on each other’s nuclear installations.

Rajiv Gandhi assassinated by suspected Tamil separatist while campaigning for seat in parliament. P. V. Narasimha Rao (Congress [I]) becomes Prime Minister of India.

Another heavy water plant commissioned at Hazira in the western Indian state of Gujarat.

1992 (February 6) Pakistan says it has acquired the technology to build a nuclear weapon.

Hindu mob destroys an historic 16th century mosque in the northern Indian town of Ayodhya, sparking Hindu-Moslem riots throughout India, resulting in 2,000 deaths.

Unit-2 of India’s Narora Atomic Power Station begins operation.

(December 26) Pakistan begins construction of 300 Mwe nuclear power plant in Punjab.

1993 Unit-1 of India’s Kakrapar atomic Power Plant begins operation.

(October) Benazir Bhutto becomes Prime Minister of Pakistan again.

1994 Unit-2 of India’s Madras Atomic Power Station goes on line.

Unit-2 of India’s Kalpakkam Atomic Power Station goes on line.

(December 26). Pakistan orders closure of India’s consulate-general in Karachi, accusing India of involvement in terrorist activity. India denies it.

1995 (January 4) India closes Karachi consulate-general.

(January 15) India asks Pakistan to reduce number of diplomats in New Delhi embassy.

1996 (January) India tests Prithvi II missile capable of carrying nuclear weapons. Pakistan says the missile is designed to attack Pakistani cities.

(March) U. S. Officials say Pakistan will conduct its first nuclear test if India conducts one.

(May 16) Atal Behari Vajpayee becomes Prime Minister of India.

(June 1) H. D. Deve Gowda becomes Prime Minister of India.

(September) UN approves Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

1997 Inder Kumar Gujral becomes Indian Prime Minister, heading a coalition government. This marks the first time an "untouchable" becomes Prime Minister.